Propofol in Routine Colonoscopy: Better Care or Better Bottom Line?

by Larissa Biggers, on July 13, 2018

What’s driving Propofol use for colonoscopy, better patient care or a better bottom line?

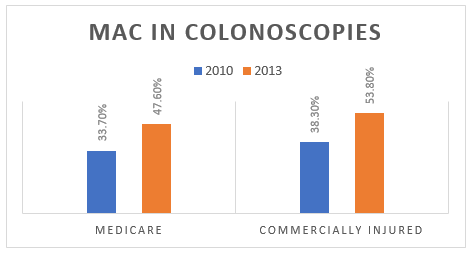

Just 10 years ago, moderate sedation—a combination of short-acting anxiety and pain medications administered by a gastroenterologist—was used in more than 80% of all colonoscopies in the U.S. Yet over the past decade, the use of deep sedation (aka, MAC) has risen sharply. A recent study of over 6.6 million patients undergoing GI procedures found that by 2010, 33.7% of Medicare patients and 38.3% of commercially insured patients received MAC for their colonoscopy. By 2013, these figures had risen to 47.6% and 53.0%, respectively. And today those numbers are even higher.

What’s Driving the Change?

Advocates for MAC sedation for colonoscopy point to increased patient and physician satisfaction as justification for widespread use. Patients under deep sedation remember nothing from their procedure. They also recover sooner due to the fast-acting nature of the drug used, Propofol. For hospitals, this means that patients can be discharged more quickly, reducing operating costs.

Increased Costs, Increased Revenue

MAC requires an anesthesiology professional to administer Propofol and to monitor the patient, which increases the cost of colonoscopy. In fact, fees associated with MAC sedation in the U.S. can add between $600 and $2,000 to the overall procedure cost for patients and insurance companies. But for healthcare facilities, higher charges to patients yield more revenue and enhanced profitability.

Risks for Patients

For patients, deep sedation can be attractive. They will likely have no memory of the procedure, and recovery time is faster. Also, patient and provider satisfaction is higher.

But consider the risks. Because deep sedation dulls response to pain, it prevents patients from providing feedback and increases the likelihood of adverse events. Specifically, there is a higher risk of traumatic injuries during colonoscopy with MAC, including perforation and splenic injury. A recent comparison was made of forces on the colonoscope during procedures performed with either 1) conscious sedation or 2) Propofol. The study demonstrated significant increases in peak and average force with Propofol. In some cases, the magnitude of force was greater than the tear and perforation forces that can be measured on surgical or cadaveric specimens.

The use of Propofol for colonoscopy has also been linked to aspiration and aspiration pneumonia because of diminished airway protective reflexes during this type of sedation.

![]()

Against ASGE Recommendations

The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) recommends MAC only for patients who do not tolerate standard sedatives used for conscious sedation, have specific comorbidities, or are at risk for airway compromise. It notes that MAC is not cost-effective for average-risk patients undergoing routine procedures.

A 2017 study published in JAMA sought to determine the extent to which financial incentives associated with MAC use might impact patient-care decisions. It looked at 3.5 million procedures performed at VA hospitals, an environment where there is no financial incentive for using MAC, and found that it was employed in fewer than 10% of all procedures. This is a remarkable finding, given that rates in fee-for-service facilities are approximately 55% of all patients.

The implication is that decisions made in traditional settings might be based on profit first and patient care second. Case in point, a study of Medicare and commercial claims data from 2010 to 2013 found that “more than half of MAC appears to be used for routine endoscopy in low-risk patients, suggesting widespread guideline-discordant use that may in part be driven by financial incentives.”

Worth It?

In an era of rising healthcare costs, spending trends for colonoscopy are headed in the wrong direction. Dr. James Scheiman, former director of endoscopic research and the advanced endoscopy training program at University of Michigan, sums up the problem: “Colonoscopy is the most cost-effective and the most effective cancer screening test we have. By doubling its cost with Propofol that equation will change.” Evidence supporting the benefits of deep sedation is limited. For screening colonoscopy in low-risk patients, the question is: Given the risks and price tag, is Propofol worth it?